The Ethics of the Boeing Groundings

a note from the author

As Boeing pushed for dominance in the airplane market, their engineering team made critical errors that greatly compromised the integrity and safety of their plane. The consequences? 346 lives. In this assignment, I will explore what went wrong and how these key errors compare to other engineering mistakes that have led to tragic deaths. Through these cases, we can learn how overconfidence in software, failure to eliminate root causes, and inadequate investigation can all lead to deadly software bugs.

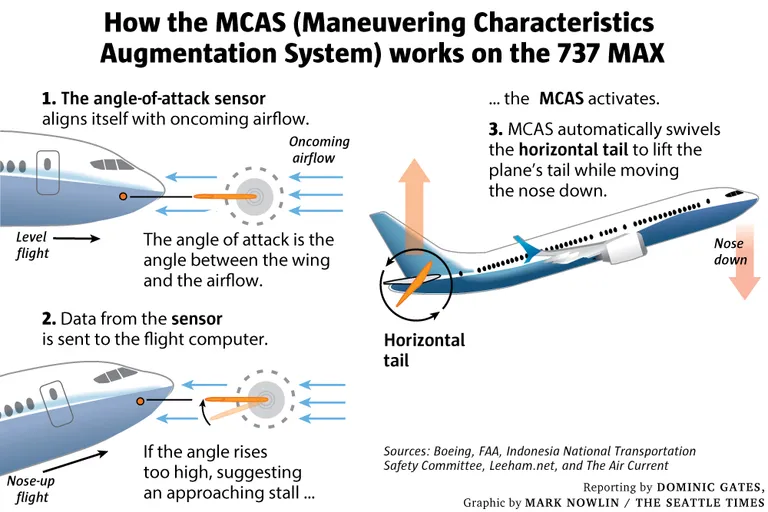

Boeing was (and still is) one of two major titans in the aircraft manufacturing market (Aviation Week Network, 2015). However, the other major player in the industry, Airbus, had been rolling out a major update to their flagship plane, the A320. This update had been in the works since 2010 and its biggest feature would be a new turbo-fan engine that was more fuel efficient, saving airlines major costs. This major shift in the market was felt by Boeing, who began rolling out their own updated plane, the 737 Max (Mouawad, 2010). There was one important detail, however. Boeing’s plane was lower to the ground than the Airbus plane. Adding a bigger engine to the 737 would cause more problems than it did for the A320. Yet, even though Boeing executives had previously said they wouldn’t re-engine the 737, in 2011 production head Mike Bair stated that his team had found a way to fit the engine under the wing (Leeham News and Analysis, 2019). Their solution was to simply move the engine higher on the wing. Boeing’s new plane saved the company from losing exclusive airline deals to Airbus (Gelles et al., 2019). Unfortunately, the change to engine position had unintended consequences. When at full thrust, the nose pointed too far upward. Boeing’s solution was MCAS (Maneuvering characteristics augmentation system). A sensor in the front of the plane would detect oncoming airflow, and this data was collected and sent to the flight computer. If the angle was too high, MCAS activated and lifted the plane’s tail upward to move the nose downward (Gates & Baker, 2019).

The problem here laid in the fact that this feature was not communicated to the public, especially pilots. So in 2018, when the plane began lurching downward on the Lion Air Flight, pilots had no idea why. As they frantically searched the manual and fought with MCAS, the plane continued to nose dive. Eventually, this led to a crash and a death toll of 189. Flight reports demonstrated evidence that the MCAS failed because of incorrect sensor data (Bellamy, 2019). The 2019 Ethiopian crash was similar, but pilots disabled the MCAS. Still, the plane was already in full nose dive at this time, too late to regain control. The crash killed 157 people (Kitroeff et al., 2019).

While these crashes were devastating, in the past we have seen similar situations where bad engineering practices have endangered and taken human lives. The Therac-25 deaths were a similar situation and the lessons learned in that investigation are also relevant to the Boeing crashes. In Nancy Leveson’s analysis of the Therac-25 accidents, she identifies “causal factors” that can be learned from these engineering mistakes (Levenson, 1995).

The first of these factors is overconfidence in software. In both cases, a general overconfidence in software played a significant role in the accidents. In Boeing’s case, the use of a single sensor was considered acceptable because engineers “calculated the probability of a ‘hazardous’ MCAS malfunction to be virtually inconceivable” (Gates & Baker, 2019). Unfortunately, the MCAS was at the mercy of its sensor, which Lion Airlines plane had replaced just two days prior to the crash (Bellamy, 2019). Not only did this overconfidence lead to the bug, but also to the lack of transparency among pilots. Boeing was so sure the MCAS was error proof that the 737 Max was marketed as nearly identical to its predecessor (Kitroeff et al., 2019). This led to a severe lack of mandated additional training for pilots flying the 737 Max for the first time. Those who flew the plane were told that it was nearly identical to previous models and were given a handbook and a two-hour iPad course as training, which had no mention of the MCAS (Kitroeff et al., 2019). Boeing assumed that pilots could handle MCAS-related issues without any information about the actual MCAS. The Therac-25 situation was similar; overconfidence in software also led to deaths in this case. Early safety analysis of the Therac-25 didn’t even test the software and any problems were written off as mistakes in the hardware (Levenson, 1995). Additionally, very little software features were actually communicated to those operating the machine, leaving them completely in the dark when errors began to ensue. While Boeing was confident in their new software and for Therac-25 the reused software, both situations show the assumption that the average operator can understand confusing software is inherently flawed.

Secondly, in both situations, there was a clear failure to eliminate root causes. In the case of the 737 Max, rather than completely redesigning the plane to fit a bigger engine, Boeing thought they could design a simple workaround, completely reliant on software. The root cause was the change in engine position, which led to side effects, including the nose pointing more upward than it should have been during full throttle. This side effect was not harmless, potentially leading to an engine stall mid-flight. Rather than eliminating the root cause, Boeing came up with a workaround: the MCAS (Gelles et al., 2019). Leveson states that in the case of the Therac-25, and similar situations, “focusing on particular software design errors is not the way to make a system safe. Virtually all complex software can be made to behave in an unexpected fashion under some conditions. There will always be another software bug” (Levenson, 1995). Her point is that while software errors will always occur, we can mitigate these effects by including hardware failsafes. While the Therac-25 incidents involved software reuse at the root cause, Boeing’s root cause was a design flaw resulting from the decision to fit a larger engine into an existing aircraft structure. However, in both cases, the 737 Max and Therac-25 lacked failsafes and relied on software to patch the root causes of the potentially deadly issues.

Finally, both cases conducted inadequate investigations when following up on accident reports. In 2018, several pilots complained the 737 Max nosing downward during flight (Aspinwall et al., 2019). Records show that one captain said it was “unconscionable” that pilots were allowed to fly the plane “without adequate training or fully disclosing information about how its systems were different from those on previous 737 models” (Aspinwall et al., 2019). This was just months before the Ethiopian Air crash. Even after the Lion Air crash, Boeing and the federal government failed to identify (or disclose) what had actually caused the crash, endangering even more lives and leading to another crash. Looking at the Therac-25, Levenson states that “the first phone call by Tim Still should have led to an extensive investigation of the events at Kennestone. Certainly, learning about the first lawsuit should have triggered an immediate response” (Levenson, 1995). While the weight of the situation and death toll differs from case to case, it’s clear that the companies should have taken heed to the early warnings and incidents that occurred. Instead, they waited until the problem became so big they couldn’t file it away. Paying close attention to previous errors and complaints could have saved lives if adequate investigations had been conducted.

In the end, we can learn a lot from the Boeing 737 Max crashes, as well as other incidents like the Therac-25. If we can eliminate these key “causal factors” (Levenson, 1995) and adhere to safe and ethical engineering practices, we can prevent senseless deaths and tragedies.

References

2019

-

- Jun 2019 · Seattle News

- Apr 2019 · The New York Times

-

- Mar 2019 · Dallas News

2015

2010

1995

- Appendix A: Medical Devices: the Therac-25Dec 1995

Liked that one?

Check these out if you haven't already: